- HOME・ホーム

-

日本語

-

About Tom Fielding Golfについて

- Teaching Philosophy

- Privacy Policy

- Tom Fielding Golf School Japan - Golf Improvement BLOG

-

Blog and News Updates

>

- How good a golfer are you right now

- How Far Should I Hit My 7 Iron?

- Most Golf Fitness Misses the Mark Completely

- The Mid Round Slump!

- Take This Quick Strike Test To See What Level You Are

- Golf Camps・ゴルフ合宿

- 2019 Summer Golf camp photo galleries

- JP-3 day / 2 night: Golf Camp 3日・2泊ゴルフ合宿

- EN-3 day / 2 night: Golf Camp

- APRIL/MAY2019 Newsletter: EN version

- February 2019 Newsletter: EN version

- February 2019 Newsletter: JP version

- Golf Fitness

- Why is change so difficult

-

Lesson Articles

>

- How To Practice Golf At Home – 6 Steps To Practicing At Home

- Internal & External focus - JP

- Pro Golfers are not that good

- 3 essentials for CONSISTENCY IN GOLF

- The Golf Swing and negative words

- Beat the Heat

- Hot Weather Guidelines

- Swing Radius

- Exclusive 4 steps for improved ball striking

- Hitting from different lies

- Weight transference

- POSTURE

- Training in different climates

- Fitness Friday: Preparing for a cold-weather round

- How far will the golf ball go in cold weather

- TrackMan: Definitive Answers at Impact and More

- Clearing the left side too early is damaging.

- The Ball Flight Laws

- Head Position

- Distance = Club Head Speed + Square Impact + launch angle

- Attention! The Pre-Shot Routine

- The Basic Skill of Chipping

- 4 stages of learning

- How to Break 90 - Part 1

- How to Break 90 #2

- How to Learn a Great Golf Swing

- Perfect Practise makes practise.

- 3 Essentials to breaking a habit

- Basic principles of exercise - Points to bring out the maximum practicing effect

- Things to consider before aiming at the flagstick

- Learnig motor skills: The GOLF Swing

- RULES OF GOLF PAGE >

- Golf Humour >

-

ゴルフスクール Menu

- 2024 SUMMER Golf Camp in Japan-EN >

- 2024SGC-JP サマーゴルフ

- Melbourne Golf Tour: March 2025

- Teaching locations: Lessons inquires & bookings >

- Trial Golf Lesson >

- 2 hole Private・貸切 training program

- 1/2 day Golf School: Kashikiri program@Morinagatakako CC

- Internet Golf Lesson >

- Testimonials Customer feedback

-

Photo / Video Gallery

- 2023 Summer gof camp photo gallery

- 2022 Summer Golf Camp - Photo Gallery

- 1 / 2 day golf camp - Photo gallery

- 2021 Summer Golf Camp - photo gallery

- 2020 Summer golf camp@ Appi Kogen Iwate prefecture

- 2019 Summer Golf camp photo gallery

- Summer golf camp 2018 photo gallery

- Photo Gallery from the Australia Vs Japan Junior challenge

- 2017 5周年のSummer golf camp-Photo/Video gallery

- 2016 4周年のSummer Golf Camp Photo Gallery

- 2015 The 3rd Summer Golf Camp @ Pelican Waters Golf Resort

- 2014 Summer Golf camp photo gallery

- 2013 Summer Golf Camp at Pelican Waters, Sunshine Coast, Queensland Australia.

- 2014 The 3rd Students Cup Pro-Am 2014 - Photo Gallery

- 2013 The 2nd Students Cup Pro-Am 2013

- Video Gallery

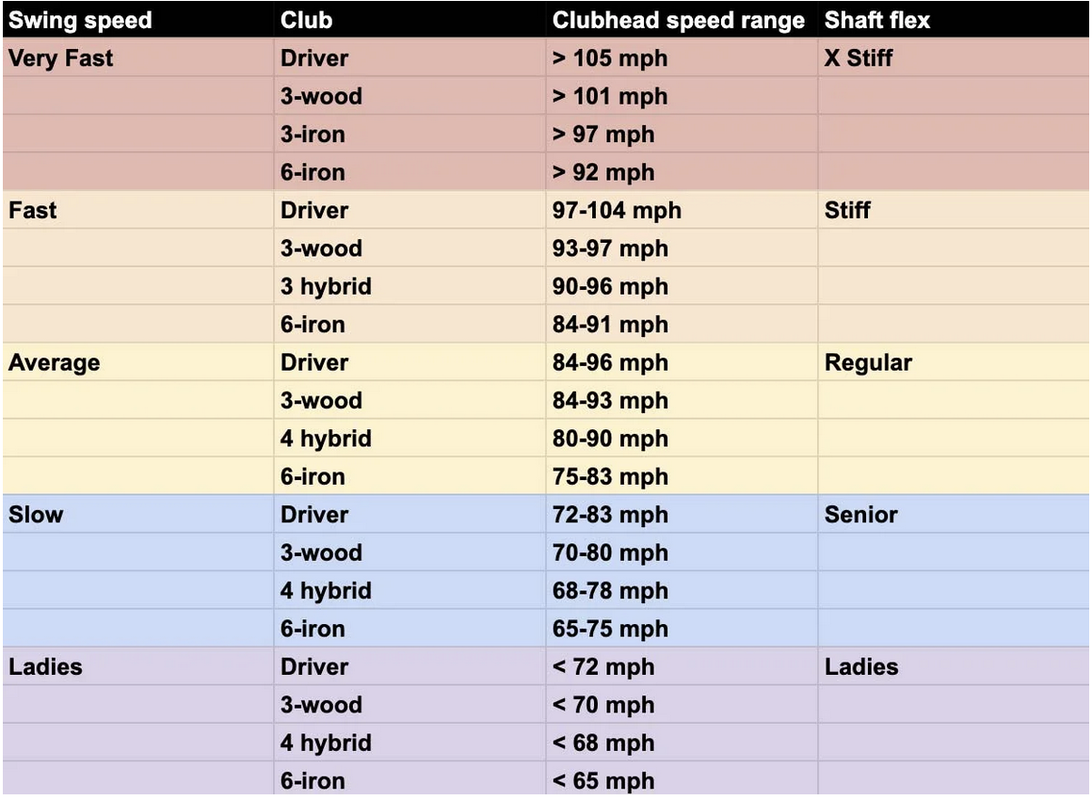

Here’s a quick breakdown of the data for drivers: Finding clubs that are right for you can be a difficult if you’re not armed with the correct knowledge. The best avenue to take when buying new clubs is going to a club fitter, but even if you don’t get fitted, you still need to be conscientious of certain variables when getting new clubs.One of the most important things you need to be aware of is what shaft flex is right for you. And although it’s not the only factor, looking at your swing speed can provide a general guideline to help you determine which shaft flex you should be playing. You should consider that your swing speed for your irons might not extrapolate perfectly to driver (and vice versa), so while a certain flex might be right in some clubs, that might not be the case in others. X-stiff – This is the range where most high-level players fall. If you’re swinging the driver above 105 mph, it might be time to get some X stiff shafts in your set.

Stiff – This range is still considered fast, but you most likely won’t be out on Tour anytime soon. If you’re between 97 and 104 mph with the driver, you need a stiff flex. Regular – Now we are getting into the range where a majority of recreational golfers fall, and also where many LPGA pros fall. If you’re between 84 and 96 mph, regular is going to be best for you. Senior – Slower swingers fall into this category. Between 72 and 83 mph signifies you need to be hitting senior flex. Ladies – By no means do all women’s golfers will fall in this category, but this is where many of the recreational women’s players find themselves. This range is going to be for anyone with a swing speed slower than 72 mph. These are all just general ranges for how swing speed translates to ideal shaft flex, but it is a good place to start. So if you can’t get to a fitter, at least figure out your swing speed and you’ll be headed in the right direction.

0 Comments

"Fore" is another word for "ahead" or "forward" - think of a ship's fore and aft. And in golf, yelling "fore" is simply a shorter way to yell "watch out ahead" (or "watch out before"). It allows golfers to be forewarned, in other words. Any golfer who hits an errant shot that sends their golf ball hurtling toward golfers ahead should yell out "fore" as a warning. When Did Golfers Start Using Fore As a Warning?"Fore" is in use by golfers around the world. One reason is that its use goes back a long time. The British Golf Museum cites an 1881 reference to "fore" in a golf book, establishing that the term was already in use at that early date (the Merriam-Webster dictionary pegs the beginning of the golf use of fore to 1878, while the USGA Museum has suggested it goes back farther). Did the Warning 'Fore!' Evolve from 'Forecaddie'?Historians at the British Golf Museum have surmised that the term "fore," as a warning in golf, evolved from "forecaddie." A forecaddie is a person who accompanies a grouping of golfers around the golf course, often going forward to be in a position to pinpoint the locations of the group members' shots. If a member of the group hit an errant shot, the thinking goes, he or she would have alerted the forecaddie by yelling out the term. It was eventually shortened to just "fore." The Military Origin of ForeAnother popular theory is that the term has a military origin. In warfare of the 17th and 18th century (a time period when golf was really taking hold in Britain), infantry advanced in formation while artillery batteries fired from behind, over the heads of the infantrymen. An artilleryman about to fire would yell "beware before," alerting nearby infantrymen to drop to the ground to avoid the shells screaming overhead. So when golfers misfired and sent their missiles - golf balls - screaming off target, "beware before" was shortened to "fore." The fact is that the origin of "fore" as a golf term of warning cannot be precisely pinned down. What can be said with certainty, however, is that the term does originate in the fact that "fore" means "ahead" or "before," and, used by a golfer, is a warning to those ahead that a golf ball is coming their way. There is a very common problem among a large percentage of middle to high handicap golfers that is called "the practice swing phenomenon."

It is the act of taking a decent practice swing and then stepping up to the ball and doing something completely different (usually significantly less decent) in the swing through the ball. It seems clear that this would not be effective and in most cases it is not. What's going on here and what can we do about it? When you take a practice swing it is fairly easy to pay attention to (be consciously aware of) what you are feeling during the swing. And since you're not going to actually hit the ball there is no particular demand on your visual system. What I believe to be happening with golfers that have a problem reproducing the positive features of their practice swings is that when they step up to the ball (now that there is a result in the balance, and the additional visual demand on the brain of the ball) the majority of the awareness is now taken away from what the golfer is feeling and put into what they are seeing, anticipating or anxious about. To recreate the same thing that happened in the practice swing they would have to continue to pay attention to what they are feeling, as they did in the practice swing. But it may even be more fundamental than that according to Dr. David Chen, Director of the Motor Behavior Lab at Cal State University, Fullerton. There is a finite amount of what Dr. Chen calls "Attention Resources," which basically means how much capacity one has for paying attention. In the practice swing without the ball these resources are not used up, but when golfers with this problem try to add the visual component, and the anxiety of an outcome, they exceed their limit in terms of how much they can pay attention to at one time, and that's the reason for a different swing with the ball. Whether it is the shift between feel and visual focus or just an overtaxed capacity for paying attention, the effect of this altered focus of attention is a host of common errors:

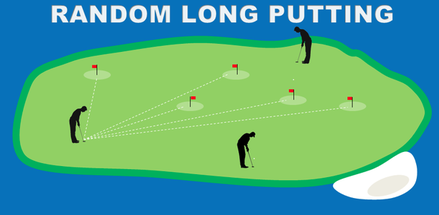

So what's the solution? One logical thing I would suggest in order to make the transition from the practice swing to the swing through the ball is to add a visual component to the practice swings: e.g., focus on brushing a leaf or particular blade of grass, etc., with your practice swings. This shows you if your club brushed the ground in the right spot or not. And if you have the specific problem of swinging too hard through the ball I would offer a temporary, band-aid type fix first: be sure to swing as hard in your practice swings as you are going to swing through the ball (and if you don't like the result of the practice swing don't swing through the ball until you take a practice swing that you like - if the practice swing was bad why would swinging through the ball on the next swing be better?). Again, this last suggestion is for temporary use; the long term solution is to groove the rhythm of your swing like a machine. Highly skilled players have the ability to pay attention to all the relevant information at the same time. Why? According to Dr. Chen they have already developed so many skills and so much awareness of what they are feeling that it does not take much of the brain's resources to pay attention to the relevant cues. Whereas the less experienced player either has not had enough time to develop those skills and awareness of the right sensations or, in the case of players who have been playing for a long time but are still functioning at a fairly low level of performance, they have never developed the fundamental skills and awareness to the point where these are automatic and, therefore, do not require much conscious attention. To develop the correct habits initially boils down to a choice, I believe. Humans have the ability to put their attention wherever they want it. If you want to develop any habit in your golf swing (for instance, keeping your spine angle constant) you have to pay attention exclusively to that one aspect of your swing until you become so intimately familiar with it that it no longer requires any conscious attention. If you just can't seem to do the same thing in your swing through the ball as in your practice swing it may simply mean that you do not have enough attention resources for the number of things you're trying to do in that small an amount of time. Again, the solution is to develop permanent correct habits (good sound fundamentals from the ground up) to decrease the demand on the attention and get things more on automatic. So work on one thing at a time until, at some point, each thing no longer requires your attention. I look forward to seeing you at our next Golf Improvement training session. Tom Fielding Australian PGA Professional Taking your Practice to the CourseOne of the common complaints I hear from my students is their inability to take their golf game to the course. They experience a certain level of proficiency on the range or practice tee but then collapse when they actually go and play. There are a couple reasons for this and hopefully, through the example here, I can shed some light on how to improve your transfer of skills. Are your golf practice sessions boring and tedious at times? You are not a golfer if you haven’t experienced these aspects of golf practice, and yes it’s true that golf practice can seem monotonous and even boring at times, however by managing the two practice styles I'm going to discuss in this article your golf practice routines will become far more challenging and a lot more enjoyable. Let's start with an important question I want you to answer honestly; "How do you know that you are practicing your golf skills the right way?" Do you favour block style practice or random style practice? You should know the difference between these two main practice styles - especially if your intention is to practice your golf skills to improve, because these different golf practice styles can help you to develop and improve the high pay-off golf skills and transfer them to the golf course faster. The Illusion of Competence Many of the amateur and professional golfers we have observed over the years lean towards practicing the style of practice known as block practice. Block practice is when you practice a single golf skill over and over to one target (like hitting chip shot after chip shot to one hole) until your practice bag or your range bucket is empty. I think you’ll agree that this type of practice is a very common way for golfers to practice? And here’s what you should know right up front about this common type of practice; block practice style is a lot like rote learning (it's very repetitive) and can lead to “the illusion of competence” where you mistakenly rate your ability when performing a certain skill repetitively much higher than it really is.  "Repeating one type of stroke over and over to the same target can improve your rhythm, tempo and timing during the session, which can influence you to believe that you are getting better at your golf skills because you are hitting lots of good shots in your session...But just be aware of the trap that this type of practice can lead you into." The Golf Practice Trap Blocked golf practice can and does influence golfers (and even their instructors) to develop a false sense of confidence (when they are preparing for a tournament) because the golfer is hitting the golf ball so well in practice that it can really increase their confidence. But it is often only short-lived as this confidence is often crushed during the tournament because the consistency and predictability of those exciting and productive practice sessions goes right out the window when shots are on the line. The research on blocked practice suggests that this type of practice does not transfer well to the golf course in competition, or lead to long-term memory retention. The simple fact is that the way you practice your golf skills really matters because when it comes down to it, the whole idea of golf practice is to transfer your golf skills successfully to the golf course and perform them to the best of your ability. In a 2011 article by Ron Kaspriske in Golf Digest magazine Kaspriske included advice from UCLA Professor Emeritus Richard Schmidt PhD and expert on motor learning who shared with attendees at the World Golf Fitness Summit that year the following advice about block practice; “In blocked practice, because the task and goal are exactly the same on each attempt, the learner simply uses the solution generated on early trials in performing the next shot. Hence, blocked practice eliminates the learner’s need to ‘solve’ the problem on every trial and the need to practice the decision-making required during a typical round of golf.” The Value of Block Practice StyleBlock practice is ideal for performing repetition practice where you might be performing a particular golf drill your instructor wants you to practice, and you need to perform lots of repetitions to develop it and habituate it to the level of unconscious competence. Block practice is extremely important for skill perfection practice, such as when you are perfecting a golf swing habit. The mental challenge level is lower in block practice as you are mainly focused on correct execution of a skill-set. This could be the perfecting of a particular drill where you are focusing on the correct feel of the drill, and using the feedback of a mirror, video or possibly your golf instructor to determine your level of accuracy at performing the skill. If you are hitting golf shots to targets, you would be hitting sets of golf shots to one target at a time with the intention of hitting many shots to reinforce consistent motion.  Block practice is very helpful for developing your techniques during the preparation phase in your golf development cycle, but is not nearly as helpful during a golf tournament cycle. The Value of Random Practice Style Random practice is quite different to block practice because you are continually varying your practice routines to improve your shot-making adaptability. You do this for example by hitting a set of golf shots to different targets that vary in the length and also in orientation to where you are on the golf range. Random is as it sounds, you continually hit different types of shots to random targets just like you get on a golf course. An example of a random practice routine would be when you hit a 7 iron to one target green, then you might hit a driver to another distance target and then a sand shot to a tight pin and so on. You are practicing adaptability which is the BIG SKILL of high performance golf. Varying your shot-making skills to include a range of shot types from short to long continuously, really helps you to develop and enhance your playing skills and ability. Random practice style is very helpful in the pre-tournament and tournament phases because it gets you out of swing thinking and improvement mode and into shot-making and feel mode. So the key to effective golf practice is to know what development cycle you are in and why. Practicing block style around tournament time isn't helpful for skill transfer as your mind-set can be too much on technique perfection and not enough on targeting adaptability.

You would be surprised at how many professional golfers are working on their techniques during a tournament cycle instead of working on it in the pre-season. You need to really think about how you are practicing your golf skills and which style you are favouring by making sure that your practice is influenced by the development cycle you are in currently. Both these styles of practice are very important and you should sit down with your golf instructor and design a practice plan that distributes the proportion of time you need for block style practice (for technical development) and balancing it out with a proportion for random style practice (targeting development). Get the mix right, and practice will never seem boring, and you will discover that the hard work on the driving range will transfer to the golf course more easily, leading to better performances and a lot more fun. Tom Fielding Golf School Japan Summer Golf Camp and Australian PGA Legend Tour Pro-Am event on the SUNSHINE COAST, QUEENSLAND, AUSTRALIA.

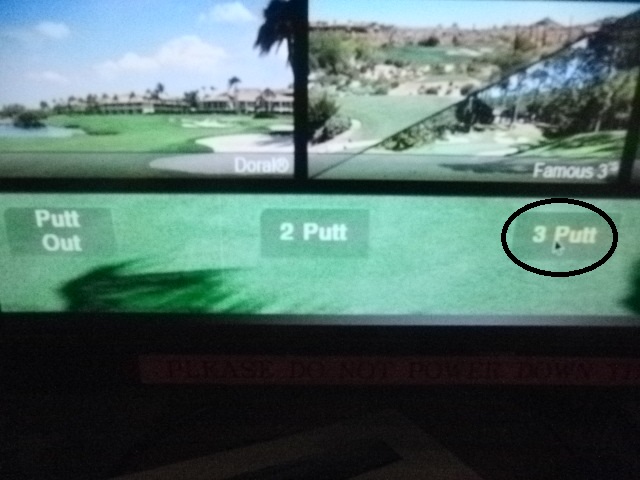

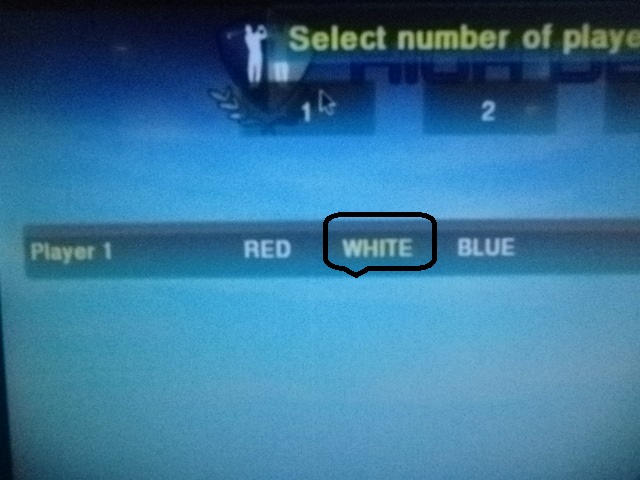

◆PROGRAM FEATURES. l Designed to allow golfers to play and practice to their heart’s content, while having the chance to improve their golf in the vast and naturally beautiful surroundings of the Australian country side. l To get a firsthand experience of how Australia has become one of the leading golf Countries in the world. l Participation in the Pelican Waters Golf Club, 2 day Australian PGA Senior Pro-Am event. You will reaffirm the basics of golf and learn new techniques by high level lessons performed by Tom Fielding. By bringing this experience back to Japan and improving on it in your daily practice, you will make progress in lowering your scores. Also, while in Australia gain some international golfing experience by taking the chance to interact with and compare your game with Aussie by playing and practice alongside the locals on a daily basis. Exploring the beautiful Caloundra city, the ocean and the beach should be wonderful memories too. In August, you may participate in the Local Club Competition Golf at the Pelican Waters Golf Club, a well as the chance to play with Australia Professional golfers in a Pro-Am which are played in the area. Take this chance to improve more in the Sunshine Coast Australia! For all Golf camp Tour Enquiries  THE GAME PLAN Par 3’s These holes will provide your best opportunity to make the one par that you need, but they can also be the holes that derail your round. Let’s discuss some specifics: 150 yards or less: These are your best opportunities to make your par. Choose the appropriate club, aim for the center of the green, and make your best swing. With a little luck, you might even make a birdie and give yourself the chance to shoot 88 or better! 150-200 yards: These are the most dangerous holes because of the temptation to go for it. Put your long irons away, and find a nice safe landing area short of the green. These holes, if well managed, are still great par opportunities because your pitch shots should be very short. 200 yards or more: Strangely, I like these holes better for our plan because there is less temptation to go for it. Find a safe landing area that will give you a nice angle into the green. There’s no requirement that you hit your 7I from the tee: if the best landing area is 140 yards away, hit your 8I followed by a 60 yard pitch. Remember that the angle of your approach can be every bit as important as the distance. Par 4’s These are your bread and butter holes for this strategy: two 7 irons, a pitch, and two putts. 300-330 yards: These holes will provide excellent opportunities to make a par, but you will need to focus on good decision making and course management. After a good tee shot, you will have 150-180 yards left. On the short end, you may consider hitting another 7I straight into the green. If there’s not too much trouble by the green, or if you’re hitting the ball very well, this can be a great choice. If you’re too far out or don’t have the confidence, consider your best wedge distance, the safest landing area, and the best angle into the green when planning your second shot. 330-370 yards: Most of your par 4’s will probably be in this range. After a good tee shot, you will want to consider what the best second shot club will be. As with the short par 4’s, consider not only your best wedge distance, but also the best angle and safest landing zone. 370-400 yards: These holes will require two strong 7I shots to get you within wedge range. Resist the urge to try to hit your 7I 170 yards off the tee, you don’t need it! Stick to the plan! If you have par 4’s that are longer than 400 yards, you’re probably playing from the wrong tees. Par 5’s Unquestionably, the Par 5’s are the holes that will most test your commitment to the plan. Your driver will beg to come out (this is why you should leave it at home!). Remain committed to the plan and you will be rewarded. Even when you hit “only” a 7I off the tee, the Par 5’s can be a great scoring opportunity. If the hole is playing 450 yards or less, you can hit your GIR with three good 7 irons. From 450-500 yards, you will have great opportunities to set up your favorite wedge distance and an optimal angle into the pin. When the holes stretch out to 500-550 yards, you will be tested: you will need four quality shots to hit the green. Remember: Keep the ball in play and aim for the center of the green. Before you go the golf course, I suggest that you use the 19th hole simulators to test out the above plan. There are 24 courses to choose from, select your preferred course, then set up this course to play from the white tees first. Then set the putting to 3 putts, this means that you have two chances at holing your putt, after that the simulator will automatically give you your third putt.

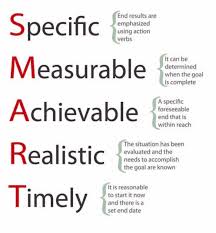

In Case of Emergency, Read This As the old boxing cliché goes, “Everyone has a plan until they get hit in the nose.” It’s easy to sit here and think about hitting every fairway and green, but what about when things go wrong? Here’s what to do and what to avoid. If you miss a fairway Don’t panic. Play a safe shot that will get the ball back in play. Advance the ball towards the hole if possible, but this is secondary to getting the ball safely back into play. If you can advance the ball to within 150 yards, play your next shot into the green. If not, lay up to your best yardage and try to make a putt. If you miss a green Don’t panic. Don’t attempt a Mickelsonian all-or-nothing shot to try to “get one back.” Play a safe shot that will get the ball onto the green and try to make a putt. If you make a double bogey Don’t panic. Stick to the plan. The only thing that has changed is that you have to make one more putt. That’s it. The course will give you plenty of opportunities for that. Bottom Line Don’t panic. Don’t deviate from the plan. If something goes wrong, get the ball back on course and try to make a putt. Conclusion I hope you’ve found this plan helpful, and I hope that some of you give it a try. It’s definitely unorthodox, but I think you will find that it is also quite effective. In the next issue, I will discuss the subject of “HOW FAR SHOULD YOU HIT YOUR GOLF CLUBS” Happy Golfing to you all Regards Tom Fielding Your Golf Coach and Golfing Guide. With the golf season winding down (or over) for many of us who live this neck of the woods, it is a time of reflection on the season that was. If you want 2015 to be better than the 2014 season, this 3-part series will tell you how to take advantage of the winter months and prepare for spring. Golf is no different than any other sport. If you want to succeed, you need to have a plan. It is extremely important to take time and evaluate your game in all aspects. If you want to improve, pull out a pen and paper and start formulating a plan for how you are going to be a better golfer next season. I recommend that you start your plan with a self-evaluation.  While personal goal setting is important, if we want to set a meaningful goal there are a few requirements that must be met. That is, the goal must be specific, measurable, and obtainable. After each of my lessons with my students, I give them a homework assignment to reinforce the learning that just took place and to provide them with some much needed feedback. On top of this I recommend that everyone keep statistics on their games, not just to count how many greens, fairways and putts but to identify the specifics of each shot. An example of what a student could bring to me could include:

Other ways is to evaluate your strengths and weaknesses of how you play your game of golf from your perspective. Be realistic about the area of your game that you want to improve. Once this list is complete, it is up to you to decide what you want to improve upon in the coming year. Obviously, we would like to get better at everything. And while I hate to burst your bubble, the reality is, that ain’t happening. So, be realistic about the area of your game that you want to improve. High-handicap players should try to stay away from evaluating how many strokes each weakness costs them during their rounds. Instead, focus on the weakness that is going to make the round much more enjoyable for you if you can improve it. In other words, if for example you average 2 to 3 putts per hole (total = 45 putts), then it would pay to evaluate the effectiveness of your chipping or pitching to gauge as a way of improving your number of putts per round. Maybe your frustrations are a result of the number of tee shots that you hit into the trees or out of bounds each round. You, then, should focus then on hitting more fairways. Naturally, improving any weakness is going to lower your scores, so worry more about fixing things that are going to allow you to enjoy yourself more while you are playing. This will help you stay motivated to practice and play as you work towards improving. For the lower handicaps, you should be doing just the opposite. Most likely, you are already playing and practicing quite regularly and shooting lower scores is motivation enough for you to put in the time that is necessary to improve. So, you should be searching your weaknesses for the areas of your game that are costing you the most strokes. For example, if your scores on par 5’s are unacceptable, an evaluation of the situation you might noticed that your second shots on those holes are a big weakness. While I’m probably only talking about four shots throughout an entire round, those four shots could very well cost you as many as five or six strokes. So, this is a weakness that you can plan to focus on strengthening for next season. For single digit and lower handicaps, your weaknesses are naturally going to be smaller and more specific. However, that makes them no less important to your game. Regardless of your handicap, I would suggest picking no more than two of your weaknesses to target for the upcoming season. Regardless of your handicap, I would suggest picking no more than two of your weaknesses to target for the upcoming season. Improving anything in your game takes time and a great deal of effort, so one or two areas of improvement are quite sufficient for a season. You do not want your goals to become an obstruction or a deterrent. A necessary level of success along the way is vital to maintaining your desire to see your plan through to the finish. Spreading out your focus to four or five goals is going to prevent you from improving any of them to the level that you desire. So, to summarize, evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of your game. You can be as specific or general as you wish. It is your game and your evaluation, so criticize as you please. Once you’ve made your list bring it with you to our next lesson so that we can check it together and then I will help you get started by selecting one or two of your weaknesses that you would like to improve. Be excited about your choices and about the potential of considering these areas to be strength instead of a weakness. Keep those positive thoughts throughout the cold and the snow and By using some analysis that you can obtain at the end of this season, this offseason you can have a specific, obtainable, and measurable goal that will help you focus and master some of your weaknesses. You can continue to improve and When spring finally does arrive, you’ll already be off to a good start! How did the size of the golf hole come to be standardized at 4.25inches?????

The “Breaking 90” Practice Plan with the Simulator

This practice plan is built entirely around learning, refining, and testing the three shots that you need to break 90. When you can complete each Test, you’re ready to take your game to the course to bag that 89. Phase 1: The Iron Shot The first thing you need to do is find out exactly how far you hit your chosen iron (let’s call it a 7I), and each club below it (8I, 9I…). Next, you need to work on your accuracy and consistency. For accuracy, make sure you’re hitting shots to a target and keeping track of where your misses go. For consistency, the goal is to hit every shot the full distance, whether that’s 150, 155, or 160 yards. Plus or minus a few yards is fine, but you can’t break 90 if you’re laying the sod over the ball. Finally, spend some of your practice time on your shorter irons. These may come into play as well, depending on the course. Test: Hit 9/10 iron shots into a 60 foot (left to right) window at least 150 yards away. Phase 2: The Pitch This is probably the most difficult part of this plan for most golfers. You will need to develop a reliable pitch shot that will allow you to hit a green from 20 to 100 yards away. The method you use does not matter: you can use Dave Pelz’s “Clock” method, a Stan Utley pitch, or whatever home brewed method you concoct. The key is reliability. You do NOT need to go flag hunting. This plan is based on hitting the green, not knocking down pins. Practice hitting shots to the biggest, safest part of the green, just like you will on the course. Part of why this is so difficult is that good short game practice facilities are hard to come by in the Tokyo region without having to drive at least one hour and half. If you don’t have one, improvise. Take some buckets or towels and place them on the range at varying distances. Just be sure to clean up after yourself. When you practice, don’t hit the same length shot over and over; this is not how you will play on the course. Hit a 50 yarder, then a 20 yarder, than a 90 yarder. Keep track of the distances that are best and worst for you. This will be important for your course management. Test: Hit the green 10/10 times from varying distances. Don’t hit the same length shot twice in a row or more than twice overall. Phase 3: The Putt The next time you are at a golf course spend some time on the putting green. The primary thing that you need to do is lag putt well and clean up your short putts, so build your practice around that. Here are some sample drills: Set up 4 balls around the hole at roughly 3 feet and make all of them. Repeat until you’ve made 20 in a row. Put 3 balls at 3’, 5’, and 7’, all on the same line, for a total of 9 balls. Make all the 3’ putts in a row, then move back to the 5’ putts then the 7’ putts. The goal is to make 9 in a row. If you miss, start over. Drop 3 balls at 30’ (or 40’, 50’, etc). Putt each of them towards a cup or a tee. If the balls end up within 3’, you win. See how many wins you can get in a row. Test: Take one ball and drop it anywhere from 10 to 60 feet from the cup. Putt it until you hole it out. Do this 18 times, from 18 different spots. If you can complete this in 36 or fewer strokes, you pass. |

- HOME・ホーム

-

日本語

-

About Tom Fielding Golfについて

- Teaching Philosophy

- Privacy Policy

- Tom Fielding Golf School Japan - Golf Improvement BLOG

-

Blog and News Updates

>

- How good a golfer are you right now

- How Far Should I Hit My 7 Iron?

- Most Golf Fitness Misses the Mark Completely

- The Mid Round Slump!

- Take This Quick Strike Test To See What Level You Are

- Golf Camps・ゴルフ合宿

- 2019 Summer Golf camp photo galleries

- JP-3 day / 2 night: Golf Camp 3日・2泊ゴルフ合宿

- EN-3 day / 2 night: Golf Camp

- APRIL/MAY2019 Newsletter: EN version

- February 2019 Newsletter: EN version

- February 2019 Newsletter: JP version

- Golf Fitness

- Why is change so difficult

-

Lesson Articles

>

- How To Practice Golf At Home – 6 Steps To Practicing At Home

- Internal & External focus - JP

- Pro Golfers are not that good

- 3 essentials for CONSISTENCY IN GOLF

- The Golf Swing and negative words

- Beat the Heat

- Hot Weather Guidelines

- Swing Radius

- Exclusive 4 steps for improved ball striking

- Hitting from different lies

- Weight transference

- POSTURE

- Training in different climates

- Fitness Friday: Preparing for a cold-weather round

- How far will the golf ball go in cold weather

- TrackMan: Definitive Answers at Impact and More

- Clearing the left side too early is damaging.

- The Ball Flight Laws

- Head Position

- Distance = Club Head Speed + Square Impact + launch angle

- Attention! The Pre-Shot Routine

- The Basic Skill of Chipping

- 4 stages of learning

- How to Break 90 - Part 1

- How to Break 90 #2

- How to Learn a Great Golf Swing

- Perfect Practise makes practise.

- 3 Essentials to breaking a habit

- Basic principles of exercise - Points to bring out the maximum practicing effect

- Things to consider before aiming at the flagstick

- Learnig motor skills: The GOLF Swing

- RULES OF GOLF PAGE >

- Golf Humour >

-

ゴルフスクール Menu

- 2024 SUMMER Golf Camp in Japan-EN >

- 2024SGC-JP サマーゴルフ

- Melbourne Golf Tour: March 2025

- Teaching locations: Lessons inquires & bookings >

- Trial Golf Lesson >

- 2 hole Private・貸切 training program

- 1/2 day Golf School: Kashikiri program@Morinagatakako CC

- Internet Golf Lesson >

- Testimonials Customer feedback

-

Photo / Video Gallery

- 2023 Summer gof camp photo gallery

- 2022 Summer Golf Camp - Photo Gallery

- 1 / 2 day golf camp - Photo gallery

- 2021 Summer Golf Camp - photo gallery

- 2020 Summer golf camp@ Appi Kogen Iwate prefecture

- 2019 Summer Golf camp photo gallery

- Summer golf camp 2018 photo gallery

- Photo Gallery from the Australia Vs Japan Junior challenge

- 2017 5周年のSummer golf camp-Photo/Video gallery

- 2016 4周年のSummer Golf Camp Photo Gallery

- 2015 The 3rd Summer Golf Camp @ Pelican Waters Golf Resort

- 2014 Summer Golf camp photo gallery

- 2013 Summer Golf Camp at Pelican Waters, Sunshine Coast, Queensland Australia.

- 2014 The 3rd Students Cup Pro-Am 2014 - Photo Gallery

- 2013 The 2nd Students Cup Pro-Am 2013

- Video Gallery

RSS Feed

RSS Feed